Key Points

- Vishwanath Nidagal from Perth runs an online group with over 22,000 members, where he shares tips for growing Indian ingredients in Australia.

- Many migrants face challenges in acquiring herbs, spices and vegetables common in their homelands.

- For some migrants, maintaining a home garden is a way of staying connected to their cultures.

“Like all migrants, I craved my traditional Indian food. I searched for vegetables we used to cook with back in India, but they were nowhere to be found. In fact, I was almost living on potatoes and lettuce for some time,” he told SBS Hindi.

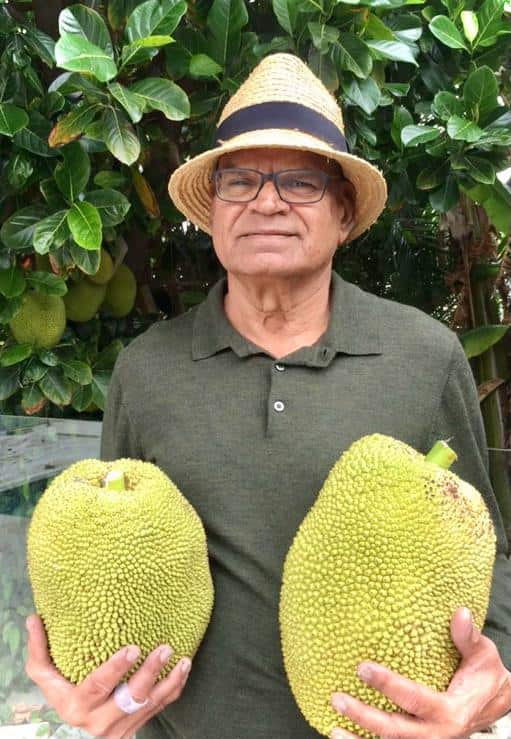

Vishwanath Nidagal with homegrown jackfruit. Credit: Supplied

As a vegetarian, Nidagal said it was difficult adjusting to a “meat-centric” country.

“Back in the ’80s and 90s, even finding basmati rice was hard,” he said.

But I took it as a challenge to cultivate these plants in my large back yard. Initially, I knew only a few basic gardening techniques, but over time, I developed more skills by connecting with a local nursery here in Perth.

Vishwanath Nidagal

“I also legally sourced many plants and seeds from Queensland, where most of them, except banana, were found.”

Images of Vishwanath Nidagal’s house.

Over time, Nidagal said his back yard was brimming with produce: black plums, mangoes, snake gourds, jackfruit, bottle gourds, eggplants, bitter gourds, and even a jasmine flower plant, which he sourced from England and paid a “hefty” quarantine fee for.

Gardening in Australia

“I stopped gardening a few years ago, but then many people started asking me how to grow Indian plants in Australia’s conditions, so I started sharing my knowledge with them,” he said.

Vegetables and fruit from Vishwanath Nidagal’s back yard. Credit: Supplied

“Some very common questions that people ask me is where to buy these plants or seeds, the best times to grow them, and which insecticide and soil to use.”

“The importation of live plants (nursery stock) and seed for sowing has the potential to introduce a range of biosecurity risks to Australia, including exotic pathogens, pests and weeds,” a department spokesperson told SBS Hindi.

Jasmine flowers grown by Vishwanath Nidagal. Credit: Supplied

A range of import conditions may then be applied, and importers must confirm that they can comply with the conditions.

“Importing non-permitted plant material or failing to comply with import conditions for permitted plants may result in export or destruction on arrival in Australia, and depending on the circumstances penalties and prosecution under biosecurity legislation may apply.”

‘I craved traditional food’

“I craved traditional food so much that I used to visit Bunnings and show them pictures of vegetables and fruits which I wanted to grow in my back yard since they were not (readily) available in the markets,” the Melbourne resident said.

Geeta Pradeep (left) grows holy basil (tulsi), tomatoes and curry leaves in her back yard. Credit: Supplied

“This (gardening) has been a way for us to fulfil our traditional food cravings. It not only helps us maintain a connection with our homeland but also allow us to share our heritage foods with others here.”

“I grow herbs such as fish wort, sawtooth coriander, and u-morok (naga chilli, one of the hottest chillies in the world). Fortunately, I found some of these herbs at Bunnings, and others were given to me by friends in Sydney, likely sourced from my Asian friends,” she said.

Melbourne-based Indira Laisram (right) and the chillies from her garden.

“The hot summers in Australia are great for growing chillies. The overall weather is suitable for these plants, and I feel fortunate in that sense.”

“I am still looking for yongchak, also known as stinky beans or petai in some Asian languages. It is used for dishes like eromba (a side dish prepared with fermented fish) and a Manipuri salad called singju,” Laisram added.

The growing visibility of the diaspora

“This trend arises from the pleasure of having these herbs at hand, the cost-effectiveness compared to purchasing them, and the convenience it offers, in addition to the pleasure of using known herbs for curries.”

Surjeet Dhanji is a researcher at the Australia India Institute. Credit: Supplied

She said there was now increased awareness of the Indian community among the wider Australian population.