EDMONTON — Vincent Desharnais needed to clear his head after the playoffs last year.

He’d just been on a roller coaster, first reaching the extreme highs of persevering to become an NHLer when few thought it was possible and then hitting the lows of some major errors in a series against the Los Angeles Kings. Ever hard on himself, it was the latter aspect that was eating away at him rather than recognizing the incredible accomplishment of the former.

So, the Edmonton Oilers defenceman decided to go on a couple of yoga retreats, the second one lasting four days outside of Sherbrooke, Que. He chose to ditch technology. Desharnais was alone with his thoughts, which were particularly apparent at night when he’d return to his room at 9 p.m. There was also a 24-hour period of silence where he didn’t talk.

“I wanted to challenge myself, to get myself out of my comfort zone — to be able to deal with that kind of stuff,” Desharnais said.

That’s when he began journalling. He chronicled any negative feelings that popped into his head.

That process has served Desharnais well throughout this season. He’s jotted down his emotions and is thinking more positively. Journal entries have often occurred postgame to document areas of improvement. Those areas to address are becoming fewer.

Desharnais has continued his upward trajectory as a reliable defenceman for the Oilers. It took him a while to get there. The 27-year-old played his 100th NHL game in Toronto last month and was the Oilers nominee by the Edmonton chapter of the Professional Hockey Writers Association for the Masterton Trophy.

After a steady campaign where he earned more responsibility, the Oilers are counting on Desharnais more than ever in the playoffs.

Evander Kane, who’s underwhelmed this season but was a goal-scoring wizard in the 2022 playoffs, and Corey Perry, a down-the-lineup player with a reputation for showing up in big moments, are forwards who could enhance the Oilers’ prospects with strong performances. Stuart Skinner’s work matters immensely as any goaltender’s does.

Desharnais, however, could be the biggest X-factor of anyone on the roster.

“I think that I have a role on this team, he said, “and I can help this team win the Stanley Cup.”

Oilers GM Ken Holland decided not to make any changes to the six regulars on defence before the trade deadline, opting to stick the same group that has primarily been in place since Desharnais made his NHL debut in January 2023. Desharnais’ personal growth and improvement factored into that decision — not to mention his 6-foot-7, 226-pound frame.

“If you look at teams that have gone on playoff runs and been Stanley Cup championship teams over the last decades, a lot of these teams have big, rangy defencemen that take up space,” Holland said.

As he aims to make amends for what happened against the Kings last April, Desharnais is determined to live and play by a mantra he’s developed during his period of self-reflection.

“I’ll talk to myself a lot about focusing on what’s in my power,” he said. “There’s so many things in life that are going to happen, so many things in hockey that are going to happen, that won’t be in your power.

“You’ve got to let them go.”

No one knows that better than Desharnais. His long and winding path to this point is filled with overcoming things that haven’t gone according to plan.

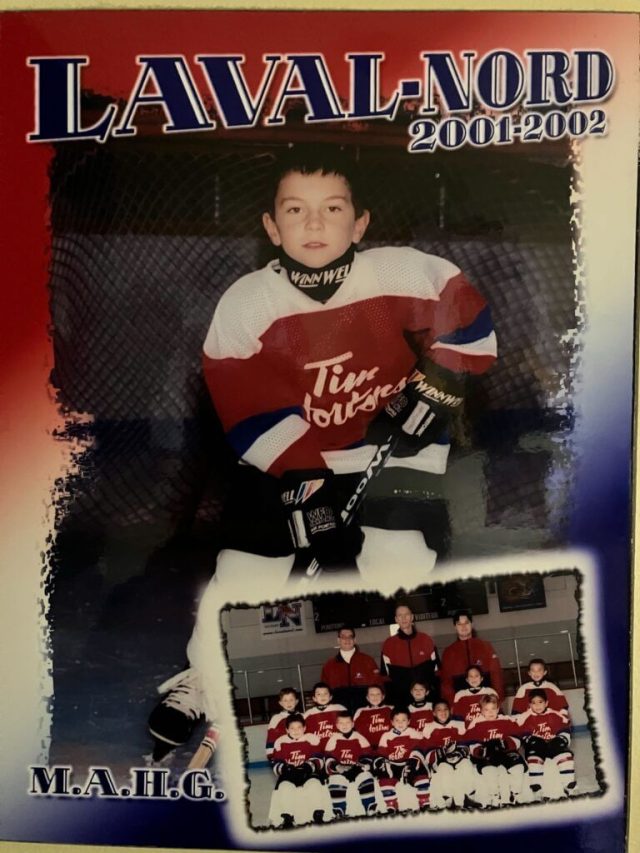

Desharnais was meant to play hockey as a child.

He grew up five houses down from the rink in his community of Laval, Que., 30 kilometres northwest of Montreal. His father, Jacques, was an accomplished defenceman in his own right. Jacques made it all the way to Detroit Red Wings training camp when he was 23 and shared the ice with Gordie Howe.

Desharnais seemed destined to follow in his father’s footsteps and those of his older brother, Alex, five years his senior. It’s just that he required a year on skates without a stick and puck first. Just imagine the now hulking defenceman known for his ferociousness taking to the ice as a figure skater at age 4.

“It didn’t stick,” he said, laughing. “But I think it helped me a little bit.”

That was just temporary, of course. Desharnais wasn’t going to have a career doing lutzes and Axels in glittery costumes. The bulky hockey gear suited him much better, though he was far from a wunderkind.

Minor hockey was when he’d first hear whispers of “Vinny’s good but not good enough,” something he still catches wind of today.

“That always drove me to get better,” he said. “Everywhere I went, I started as the seventh, eighth or ninth D-man and made my way through.”

A growth spurt at 14 helped. Desharnais was good enough that he attended a hockey prep school, Ulysse Académie, just north of Laval in his QMJHL draft year — and good enough that he was in the running to be selected by a major junior team. He attended the 2012 draft in Quebec City along with four of his teammates.

Desharnais sat there through 14 rounds as 254 players were picked, including each of his Ulysse buddies. His name wasn’t called. Desharnais said he was “heartbroken.” But he supported his teammates by taking pictures with them in their new jerseys as he fought back tears.

“It was tough to keep it together,” he said.

The ride home was even more painful.

“It was a two-hour drive,” his mother, Josée Legault recalled. “He was crying in the car.”

“It was probably the biggest blessing in disguise for me,” Desharnais said.

His goal was to prove those in the Q made a big mistake by not calling his name on draft day. Thus began the long and unconventional road.

A little more than a year later, Desharnais was off to Northwood School in Lake Placid, N.Y., to find stronger competition while pursuing his education. There was a problem. Desharnais barely spoke any English — “I knew yes and no, and that was pretty much it” — and was suddenly in a place where that was basically the only language used.

He’d call his parents often during those first few weeks. He’d sometimes be crying. Other times, he pleaded with them to come pick him up. Legault almost did, but Jacques convinced her otherwise.

Eventually, Desharnais settled in and eyed his next step.

“I wanted to go to college so bad,” he said.

Desharnais moved across the continent to play for the Chilliwack Chiefs of the British Columbia Hockey League the next season. It was there that he really grew into his own.

He showed up at the front doorstep of Terry and Matt Janssens, his new billet parents, in the wee hours of the morning after hitching a ride from Calgary with a new teammate. Terry met him and welcomed him to his new home.

There was an instant connection. Terry said they wanted a French-speaking player because Matt, an RCMP emergency response team officer, was trying to improve his mastery of the language. Terry still affectionately calls him “Frenchie,” a term Desharnais frequently uses himself.

He was originally given the keys to a sedan that he could take as needed. That didn’t work out because it was a standard transmission, and he couldn’t figure out how to drive it. Instead, the minivan became his regular wheels, which meant he routinely drove around Terry and Matt’s son, Jake, then 12, and daughter, Jenna, then 9, to school and hockey and soccer games. Terry jokes Desharnais could have had a different career as a chauffeur.

“What you see with Vinny is what you get,” Terry said. “He’s so loyal. He fit right into our family — like he’s always been here.”

“I felt like a big brother,” Desharnais said. “I’ve always been the younger brother.”

Desharnais was really thrust into that role when Terry’s mom died. Terry, Matt, Jake and Jenna were just about to arrive home from a weekend tournament when she got a call with the awful news. With Desharnais waiting at the house for them, Terry and Matt walked in scrambling. Facing a 300-kilometre drive east to Penticton, what should they do with Jake and Jenna?

Desharnais just looked at them and gave a stern but reassuring message: “I’ve got the kids.”

“That’s the first time I got the glare,” Terry said, referring to the I’m-serious look he gives on the ice.

Terry and Matt knew he could handle it. They never gave it a second thought that they’d be leaving Jake and Jenna with an 18-year-old.

“He took over everything for us,” Terry said. “It was so nice that I didn’t have to worry.”

Desharnais took control when they left. He made sure they did their homework and he got up earlier than usual — 5:30 each morning — to get himself prepared to get them to school. He also put his own spin on parenting. No, he won’t win any awards for his cuisine — there was a lot of Kraft Dinner and pop — or for allowing them to watch movies while they ate, but he more than received a passing grade.

“I was just trying to cheer them up,” he said. “It was a cool experience. It was the least I could do for them (Terry and Matt) because they were so great to me.”

Desharnais with Matt, Terry, Jenna and Jake Janssens after a game in Vancouver. (Photo courtesy of Terry Janssen)

On the ice, Desharnais made huge strides. There were some early struggles — to the point where he thought he might be sent to Junior B — but he was named top defenceman by the end of the season. The plan was for him to return to Chilliwack, but Providence College came calling earlier than expected.

Desharnais didn’t play much in his freshman NCAA season, just 19 games, but he was determined to improve his skills.

“No one believes in Vinny the way Vinny believes in Vinny,” then-Providence assistant coach Scott Borek said.

Borek worked with the teenage blueliner after every practice to try to improve his skating and angles. Getting Desharnais to open his hips was the biggest area of focus. They’d chew up the referees’ circle as part of their drills.

“I’ve always trusted myself,” Desharnais said. “But I always needed a little bit of a push, a little bit of a confidence booster from other people. Scotty was that.

“He was one of the only people who believed in me.”

“The most important skill is making sure the guy with the whistle wants to coach you,” Borek said. “Vinny is one of those guys that you die to coach.”

Desharnais made great strides, but his season was unremarkable because of limited game action. Already passed over twice for the NHL Draft, he wasn’t getting his hopes up ahead of the 2016 selections even though he’d heard from a few teams that season.

He spent the draft weekend at his brother’s lake house and, out of intrigue, followed along in the later rounds on his phone. Suddenly, he got a call, and he went to take it in private. It was Oilers director of player development Rick Carriere. Desharnais was stunned. He hadn’t been contacted by the Oilers all season, yet they drafted him with the 183rd pick.

Before he hung up, Desharnais made a declaration to Carriere.

“I know I’m a seventh-rounder, but I’m going to prove to you that you made the right decision,” Desharnais told him. “I remembered that. I’m a man of my word.”

Desharnais got off the phone and went to see his older brother, Alex. Since Desharnais had tears in his eyes, Alex assumed the worst. He started into a pep talk about how being drafted didn’t really matter. Desharnais cut him off to give him the good news. They embraced in a moment they’ll never forget.

Desharnais spent the next three seasons rising the ranks on the Providence defence corps. By his senior year, he was the captain and guided the Friars to a regional title.

“He led the charge,” said Buffalo Sabres defenceman Jacob Bryson, Desharnais’ defence partner that season. “Everyone liked him — one of those guys where you never heard a negative thing about him. Every time you saw him, he put a smile on your face.”

Borek can attest to that. Though Borek moved on to Merrimack College to be a head coach that season, Desharnais never forgot about the role he played in helping him.

As Desharnais skated around the win, he noticed Borek in the stands, near the glass at Providence’s home rink and gave him a nod of appreciation. They’d been through so much together from the extra post-practice work to Desharnais always making sure Borek knew he was there to talk after Borek’s son, Gordon, died in a car crash in 2016.

“He never lost his humility,” Borek said. “He included me in the celebration a little bit. That made me proud.”

With his collegiate career over and his degree in business management and finance secured, it was time for Desharnais to turn pro after the 2018-19 season.

Peter Chiarelli, the general manager who was in charge when the Oilers drafted Desharnais, had told him earlier that season the Oilers were planning to sign him to an entry-level contract. But Chiarelli was fired that January and Holland, his successor, didn’t know much about the hulking defenceman. Holland said then-director of player development Scott Howson recommended the Oilers offer Desharnais an AHL deal — which didn’t materialize until July.

Desharnais could have waited another month and signed a more lucrative contract with stronger NHL prospects with another team. He said he wanted to be loyal to the Oilers and felt like it was the best fit.

“I had this feeling about Edmonton,” he said.

So, Desharnais showed up in Edmonton for training camp in the late summer of 2019 completely off the radar. Within weeks, he was in the ECHL in Wichita, Kan.

While there, he got to know goaltender Stuart Skinner, who had been demoted from the AHL right before Christmas. The two players lived together for the couple weeks Skinner was there.

Skinner’s first start was a mess, an 8-2 drubbing at the hands of the Utah Grizzlies. Desharnais was minus-2. As they sat around in the living room playing video games before their next game, they hit pause and had a frank conversation. What are we doing here? Why are we doing this?

They made a pact that they’d push each other to be better. They also decided to have some fun while doing it. Born was the postgame high-five after wins that have become as much a staple of Oilers victories as the blaring of “La Bamba,” a tribute to the late Joey Moss.

“Those times really helped us grow up,” Skinner said. “It ultimately made us make a decision whether we want to go for it or not — whether we want to give up or absolutely go for it. We both obviously agreed to go for it.”

“When you’re two people in the same boat, you don’t feel as lonely,” Desharnais said.

Desharnais, in particular, still had a long way to go.

He spent 31 games in Wichita that season and played six contests for the Thunder the following campaign. By the end of the COVID-impacted 2021 season, he was a regular for the AHL’s Bakersfield Condors. But that wasn’t enough to earn Desharnais an NHL contract. He signed another AHL deal before the season ended.

It wasn’t until near the end of the following season, 2021-22, that Desharnais thought making the NHL was truly possible. He led the AHL with a plus-36 rating. Assistant coach Dave Manson was constantly offering encouragement and reassured him that he was close to making the Oilers. (Manson and Jay Woodcroft were promoted in February of that season.) Desharnais got that elusive NHL contract that March. Holland said the only thing that prevented the Oilers from playing him in a game late that season was that it would have made him waivers eligible for 2022-23.

With the Oilers sputtering last January, Desharnais was called up for his first NHL game in Anaheim. Jacques and Josée booked their flights as quickly as they could. Alex dropped everything at work — he’s in the heavy equipment sector in Lac-Mégantic, Que. — to make the game. Alex’s girlfriend Monika Trépanier made the trip, too.

“During warmups, I got the rookie lap,” he said. “There’s a picture I have of me jumping on the ice and looking up, and the first person I saw was my brother with both arms in the air and tears coming down his eyes.”

It was a dream come true for Desharnais and his family.

“Everyone was crying,” Legault said. “We were so proud of Vin and all the work he had done.”

But for a brief demotion to Bakersfield for cap reasons last February, Desharnais has been a mainstay with the Oilers and has mostly shown continual improvement.

Vincent after his first NHL game in January 2023 with his parents Jacques and Josée, his brother Alex, and his brother’s partner Monika. (Photo courtesy of Josée Legault)

The start of last year’s playoffs couldn’t have been much worse for Desharnais.

He took a tripping penalty in overtime in Game 1 and the Kings scored on the power play to win the series opener. Game 4 was disastrous. He was burned on three goals against in the first period and was benched as the Oilers came back and won in overtime.

“It was hard because I’m such a such a perfectionist,” Desharnais said. “I don’t want to let my teammates down. I want to be the best person I can be, the best player I can be.

“It was tough mentally to deal with all that. I’d make one mistake and it felt it was the end of the world.”

Desharnais was in his own head after Game 4. Mattias Ekholm pulled Desharnais aside and told him he’d had worse games than that earlier in his career. He instructed Desharnais to keep his chin up, that the Oilers still needed him.

“You’re going to get punched in the face, but you’re going to have to stand up the next game or the next time and do it all again,” Ekholm said, recalling that conversation. “Sometimes it’s good for a young player to do that, just to feel that it’s OK. Mistakes are going to happen.”

Desharnais said he took Ekholm’s advice to heart. That helped him rebound in the Vegas series and, after clearing his head in the summer, he came to training camp with a steely resolve. It appeared that the Oilers’ preference was to have top prospect Philip Broberg, Desharnais’ former Bakersfield roommate, become a regular. But Desharnais, as he’s been wont to do, wasn’t going to roll over.

“He has a lot of belief in himself and a lot of determination,” Holland said. “He understands what he needs to do to contribute to be on the team. That’s a real strength.”

“That’s what happened at Providence,” Borek said. “He makes it impossible not to put him in. And once he gets in, it’s almost impossible to get him out.”

Desharnais missed just four games all season — two as a scratch so Broberg could get in the lineup in the first month and two after a fight against Colorado’s Josh Manson in March. He’s been a regular on the penalty kill. At even strength, he’s largely been half of a solid third pair with Brett Kulak, but he got a trial run next to Darnell Nurse last month.

“He’s got a lot more confidence with the puck,” Nurse said. “He’s got a lot of confidence defending.”

“He’s a huge part of this team,” Ekholm said. “He’s taken steps. Every department of his game has grown. Him pushing us in the top four has been huge as well. It helps us be better. For him to be knocking on the door, pretty much all year, that just creates a healthy competition on the team.”

Desharnais is a pending unrestricted free agent. The contract talks between Holland and Desharnais’ agent Phil Lecavalier have been halted because of the playoffs. The expectation is the defenceman will be re-signed after the postseason, provided negotiations don’t go off the rails.

“We’d like to keep him,” Holland said.

Desharnais looks so much different now than he did in that Kings series a year ago.

For one thing, he’s got flowing black hair with specs of grey approaching the bottom of his neck when last year he sported a bald look. Desharnais will shave his head in the summer to, once again, raise money for Leucan — a Quebec-based charity to support children diagnosed with cancer.

On the ice, Desharnais is a different version, a better one, of his same self.

“He knows his job, and he just does it,” Skinner said. “He plays very much of a man’s game out there. I think about how much he’s helped me. The things that he does in front of me is just beyond me. How he can just block that many shots for me on the PK. It’s a thankless job. The ice packs that this guy wears after every game is just incredible.”

Desharnais feels the trust his teammates have in him. That’s when he’s always been at his best.

“I’m fuelled by people believing in me,” he said.

He’ll also have tons of support from those around him.

His parents are coming to Edmonton for the start of the playoffs and will be at as many games as possible.

Terry will be watching from Chilliwack, often from “Vinny’s hot tub.” The Janssens were waffling on whether to get a hot tub when Desharnais lived with them, and he convinced them to take the plunge.

Borek will catch as many games as he can, too. Regardless of what happens in the days and weeks ahead for Desharnais, Borek is sure the best is yet to come.

“He hasn’t arrived yet,” Borek said. “He’ll never feel that way.”

One thing’s for sure, he won’t be in his own head like he was against the Kings last year.

“When I feel like I’m uncomfortable and losing control a little bit, I know how to get back to controlling it,” Desharnais said. “I know how to control one thing — that’s me and my brain.”

(Photo of Stuart Skinner and Vincent Desharnais: Steven Bisig / USA Today)